The Legacy of Images; Pt. 3-Giovanni Battista Piranesi

Written by Jacob Urban.

This article originally appeared on the Blueprint South Dakota blog on March 20, 2019.

Drawing and the production of images underpins nearly every effort made as an architect. It is the means by which architects not only describe a concept, but the internal manner in which a concept is initially formulated, and subsequently refined. The ability to think critically through drawing is not exclusive to Architecture, however it is undeniably essential to the broader goal of expressing a proposed thought or idea. Architecture’s reliance on images and drawing conceals a strange consent to the limitations of language. As intricate and expressive as language may be, it can often seem an inappropriate device for describing the subtle complexities inherent in a given concept. Thus, clarification necessitates an image, a nearly universally-accessible means by which those within, and more importantly apart from the discourse of Architecture can intuit the intentions of the architect. Given the requisite nature of the image as a measure of communication, the fundamental importance of drawing becomes clear. What follows is a brief description of a particular individual whose involvement in the discipline of Architecture helped to advance or elevate the tradition of visual communication, image-making, and drawing.

Giovanni Battista Piranesi was born in 1720, in the Republic of Venice. Despite having spent his early years there, Piranesi would eventually develop an irrevocable association with Rome, not just because he spent the majority of his life in the capital of the ancient empire, but because it also served as the conceptual and thematic focus of the majority of work produced throughout his lifetime. An abbreviated description of Piranesi’s career would categorize him as an artist who worked primarily through etchings and engravings, however a broader and more detailed explanation of his work would include the role he played as an archaeologist, conservationist, cartographer, and public intellectual. The sentiment of profound admiration and artistic interest in Rome, described in the preceding articles, had been firmly established by the time Piranesi emerged on the stage of architectural history. As such, he dedicated his life to a fevered documentation of the vestiges of classical Roman architecture, and their succeeding dissemination throughout a European citizenry, increasingly influenced by the scientific-awareness of the Enlightenment era.

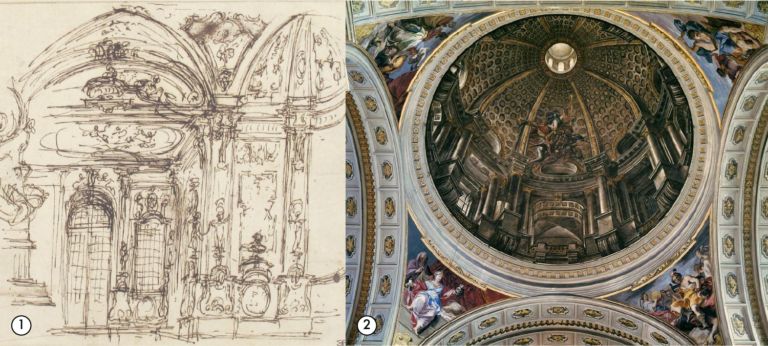

The formative half of Piranesi’s career is characterized by a collaborative contribution to several high-profile projects, most of which were distinguished as having some urban or cartographic thesis at their core. While still living in Venice, Piranesi found work in the studio of Giuseppe Zucchi, an engraver specializing in the production of ephemeral scenographic images of the city. As was common at the time, the production of an engraving required the sequential involvement of several individuals; an artist to produce an initial image, a craftsman to manufacture a copper plate, a colorist to finalize the image, etc. In this capacity, Piranesi was tasked with resolving the perspectival mathematics of the initial drawing, prior to its embellishment and eventual printing. The experience Piranesi gained in this position was compounded at his next job, working for Giuseppe and Carlo Valeriani. The two brothers operated an architecture studio, working almost exclusively in interior work for wealthy clientele throughout Europe. Much of the embellishment and ornamentation which distinguished their designs, were actually achieved through trompe-l’oeil, or the clever painting of objects onto a flat surface for the purpose of illusion. This complex task fell to Piranesi, who would develop the perspectival geometry, and calculate the shadows required to create a convincing ruse.

2. (trompe-l’oeil perspective) Dome of Chiesa di Sant’Ignazio di Loyola, Andrea Pozzo, 1685

Piranesi’s status as an authority on urban representation began to develop in earnest when he was invited to work for the architect and surveyor Giambattista Nolli. In 1736, Nolli was commissioned by Pope Benedict XIV to survey Rome and produce a map which could be used to guide in the increasing architectural development of the city. The map took 12 years to complete, and would become one of the most reproduced documents in cartographic history. Incidentally, the map was used as late as the 1970s for urban planning and infrastructural development. Piranesi’s role in its production was to produce the illustrations of prominent Roman ruins which adorned the margins of the map. Prior to the completion of the Nolli Map, Piranesi left the project to work for Charles III of Spain, who employed his assistance in the reproduction of the Forma Urbis Romae, as a gift to the Pope. Originally contracted by Emperor Septimius Severus in 200 AD, the Forma Urbis Romae measured 43’ by 60’ and was composed of 150 marble slabs. The map was an unprecedentedly thorough catalog of Rome’s public buildings and ultimately the earliest indication of the city’s urban and administrative organization. Due to the unfortunate tendency for Roman ruins to be salvaged for their materials, only about ten percent of the original map existed in the 1700s. Piranesi illustrated these remaining fragments in conjectural adjacency to the city’s present layout, eventually producing Alcuni frammenti della Forma in una incisione di Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1756).

4. Alcuni frammenti della Forma in una incisione di Giovanni Battista Piranesi, 1756

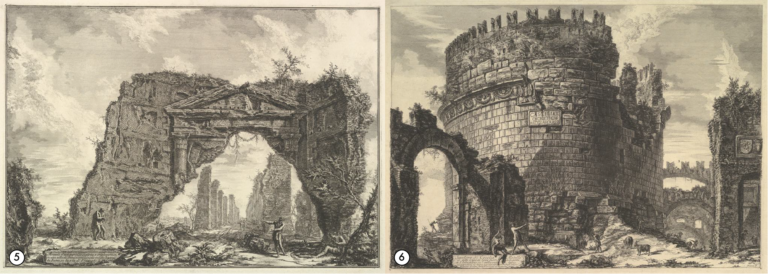

By this point, Piranesi’s reputation as an expert on Roman antiquity had been firmly established, and in 1760, he had accumulated sufficient social and financial capital to establish his own printing studio in the Palazzo Tomati. Having his own studio allowed him to disseminate the vedute, or highly-detailed large-scale depictions of urban spaces, that he had been developing since his arrival in Rome some years earlier. The practice of creating vedute had already been established prior to the inception of Piranesi’s career, however his approach to the medium was unique in its focus on the subjective, experiential qualities of the spaces he was depicting. The monumental characteristics of the surviving ruins of Rome produced a profound emotional response in Piranesi, which he was able to communicate through his representation of urban spaces, often times at the expense of proportional accuracy. In an attempt to represent the visceral reaction one would have at experiencing the architecture of Rome, Piranesi would frequently exaggerate the scale of monuments, or subtly adjust the horizon-line in a composition, for the purpose of dramatizing its overall appearance (a feat which could only be performed by someone highly skilled in the mechanics of linear perspective). However, these liberties taken in compositional construction were not merely a means of architectural-fetishization, but rather an appeal to the hitherto unrealized emotional component of architecture. In 1730, as a result of artistic and economic investment, Rome was beginning to experience rapid urban development, and was quickly becoming a tourist destination for wealthy Europeans, and scholars. These visitors to the city generally brought with them a lavish propensity for spending, and an appetite for ephemeral objects which could be brought back to their respective countries and serve as reminders of their experience. Piranesi’s vedute, with their emphasis on the experiential component of architecture, not only satisfied this demand, but also served to advertise the qualities of the city for those living beyond Rome’s borders.

6. The tomb of Caecilia Metella, from Vedute di Roma, Giovanni Piranesi, 1762

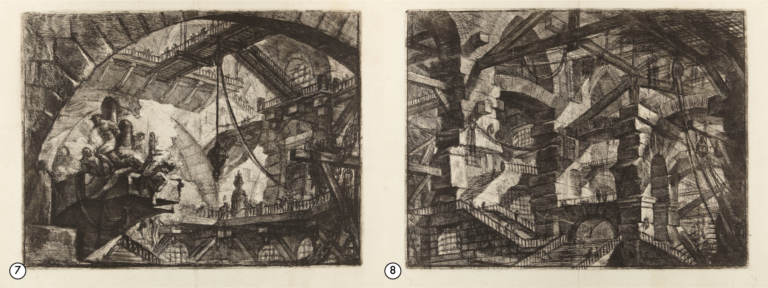

Whether one interprets Piranesi’s tendency to contort the qualities of his architectural subjects as an appeal to market-demands, or a deliberate stylistic choice, the profitable results of his frenetic production created the circumstances in which he was able to indulge his more thematic artistic interests. In 1761, Piranesi produced the second edition of Carceri d’invenzione, (imaginary prisons) which would arguably become his most enduring contribution to the tradition of architectural representation. The publication is a series of sixteen etchings depicting a monumentally vast subterranean prison, in which the conventions of perspective and scale are disregarded for the sake of creating a composition imbued with ambiguity and ominous wonderment. Despite the inclusion of architectural elements which would have been familiar to the viewer, their application is represented in an unapologetically implausible fashion. Imaginative traces of a mysterious narrative pervade each etching in a way that compels the viewer deeper into an increasingly complex composition. Perhaps the most disconcerting quality of the images is the manner in which the broader inexplicable themes are visually executed with a degree of meticulous detail. In the words of Aldous Huxley, “Piranesi’s prisoners, are the inhabitants of a hell, which, though but one out of innumerable worst of all possible worlds, is completely credible and bears the stamp of an unquestionable authenticity.”

8. The Gothic Arch, Carceri d’invenzione, Giovanni Piranesi, 1761

For those who study the work of Piranesi and his contemporaries, it can be a challenge to resolve the relationship between the admittedly darker themes of Carceri d’invenzione, with those of his larger oeuvre, however a clue can be gleaned by examining the differences between the first and second editions. In the initial publication of the work, the interplay between light and shadow is less dramatic and the inclusion of much of the detailing which produces its forbidding atmosphere is absent. One is inclined to reflect on the circumstances which might have produced this distinction. Running concurrently to the rise in popularity of Enlightenment thinking was an interest in the sublime. It stands to reason that as the world was becoming increasingly demystified, people began to articulate a nostalgia for an aesthetic which could represent their former sense of wonder. The work produced in the later hours of Piranesi’s career occupies this space, alongside a host of other artists and writers whose contributions coincided with the rise in popularity of the Gothic novel, and its adjacent visual aesthetic. With less than a century between them, Carceri d’invenzione thematically predicts the work of artists such as Henry Fuseli, whose painting, Nightmare, evokes themes of dark, irrational forces, and foreshadows the emergence of psychoanalytic theory in the century to follow. In a broader sense, Piranesi’s work can be said to have prefigured the emergence of Romanticism, a visual and literary movement which originated in the late 18th century, and emphasized the emotional power of nature, the poignancy of sensory experience, and of course, the existential implications of ancient ruins.

10. The Nightmare, Henry Fuseli, 1781

In summarizing the significance of Piranesi’s artistic accomplishments, it is acutely difficult to succinctly address all the ways in which the culture and tradition of drawing and image-making was affected by his work. Any particular contribution merits substantial applause, but when viewed in its entirety, one is hard-pressed to imagine how representational production would have proceeded in his absence. All artistic advancements are sequentially reactive, whether sympathetic or otherwise. Would the art of architectural representation have stymied in its preceding trajectory, or would it have deviated tangentially in some less than imaginative direction? Against the backdrop of this premise, it can at least be known with certainty that the aforementioned traditions have only benefited from the contributions of Giovanni Battista Piranesi.